The Genius Behind MLS and the Future of E2EE Messaging

It's about time instant messaging got the TLS treatment.

What's in a protocol?

In this day and age, privacy has become something of a necessity in the face of mass digital surveillance and data harvesting. Messaging apps like Signal and Session champion the privacy-first ethos through end-to-end encryption, whereby only the sender and intended recipient(s) can read their communications. As these privacy concerns come to the forefront of our increasingly digital lives, intelligent people are finding ways to standardise secure messaging for the masses.

With this in mind, there are three (ish) main things to consider if you want to build an end-to-end encrypted (E2EE) instant messaging app.

Forward Secrecy- If a long-term key is compromised, an attacker shouldn't be able to derive past keys. Prior communications should remain secure.Post-Compromise Security- If a long-term key is compromised, an attacker shouldn't be able to decrypt future communications indefinitely. Dubbed the "self-healing" property, it means that in the event of a compromise, at some point the protocol will recover by regenerating key material, locking out the attacker.-

Scalability- Group chats are quickly becoming the medium of choice for communication for organisational and recreational purposes (see Teams, Slack, Matrix). As the size of a group grows into the thousands, guaranteeing either of the previous two principles can become computationally expensive. -

KEM-agnosticism(Honourable Mention) - Protocols shouldn't be reliant on one specific cipher-suite/KEM to function. They should be interchangeable for both compatibility and resilience purposes. At any point some researcher can drop a paper demonstrating a devastating cryptanalytic attack that obliterates the security of your KEM. A great example is the Supersingular Isogenic Diffie Hellman Key Exchange algorithm (SIKE). SIKE was a very promising quantum-resistant successor to the classic Diffie Hellman Key Exchange that withstood a decade of cryptanalysis - until the summer of '22, when cryptographers found a key-recovery attack so devastating that it pretty much killed the field of isogeny-based cryptography. Fly high SIKE 🕊️

Combining all of the above turns out to be quite challenging.

A brief history

Previous attempts at implementing E2EE for instant messaging have been quite successful. One could argue that the Off-The-Record messaging (OTR) protocol was the first serious go (not counting PGP since it was designed for email). This protocol brought deniable authentication and forward secrecy to messaging services - but no group messaging. Group messaging was proposed in 2009 (see mpOTR), but exists as little more than a proposal.

Then came the Signal protocol of Signal app fame, which combined the best of OTR and the Silent Circle Instant Messaging Protocol (SCIMP). It uses the brilliant Double Ratchet Algorithm to provide both forward secrecy and post-compromise security. Additionally, it introduced the Extended Triple Diffie-Hellman algorithm for asynchronous/offline messaging, allowing users to send messages securely when the recipient is offline. So cool! However, the double ratchet was only designed for 1:1 communication - having pairwise encryption for each group member it not ideal (this Computerphile video explains the issue quite well). Although they actually considered implementing mpOTR, group messaging in Signal is done using the TextSecure Group Protocol, which implements a hyper-optimised pairwise double-rachet system to compensate for the overhead. And while it does work just fine, the rise of large-scale group chats with frequent state changes (members joining, leaving etc) indicated the need for something more robust.

There are also the Olm and Megolm cryptosystems used by the decentralised Matrix protocol. Olm and its group-messaging counterpart Megolm use a ratchet mechanisms based off Signal, but NCC Group's cryptographic review found Megolm lacked sufficient forward secrecy and post-compromise security. Rats!

Admiring ART

It was around 2017 that Meta researchers introduced the Asynchronous Ratcheting Tree, a proof-of-concept protocol that used a binary tree structure to efficiently manage asynchronous group-based key exchange at scale, without compromising on forward/backward secrecy. The real kicker of this approach is that changes to group state/secrets (e.g. members leaving, joining, refreshing) occur in O(log(n)) time, as opposed to O(n²) in the worst case for pairwise systems!

This eventually led to the Messaging Layer Security (MLS) protocol (RFC 9420), published in 2023, which utilises async ratcheting trees for scalable group key management.

Messaging Layer Security (MLS)

MLS was designed with the intention of becoming the E2EE instant messaging security layer to end all E2EE instant messaging security layers. As adoption of instant messaging as a medium grows, the underlying protocols will have to be both secure and efficient at scale.

MLS aims to kill all of these birds with one carefully considered stone, and can be split into three sub-protocols:

TreeSync, which synchronises the group's state (ratchet tree) amongst membersTreeKEM, which handles key management/evolutionTreeDEM, which uses said keys to encrypt messages

Note: I won't go into TreeSync or TreeDEM to avoid being out of my depth thrice over.

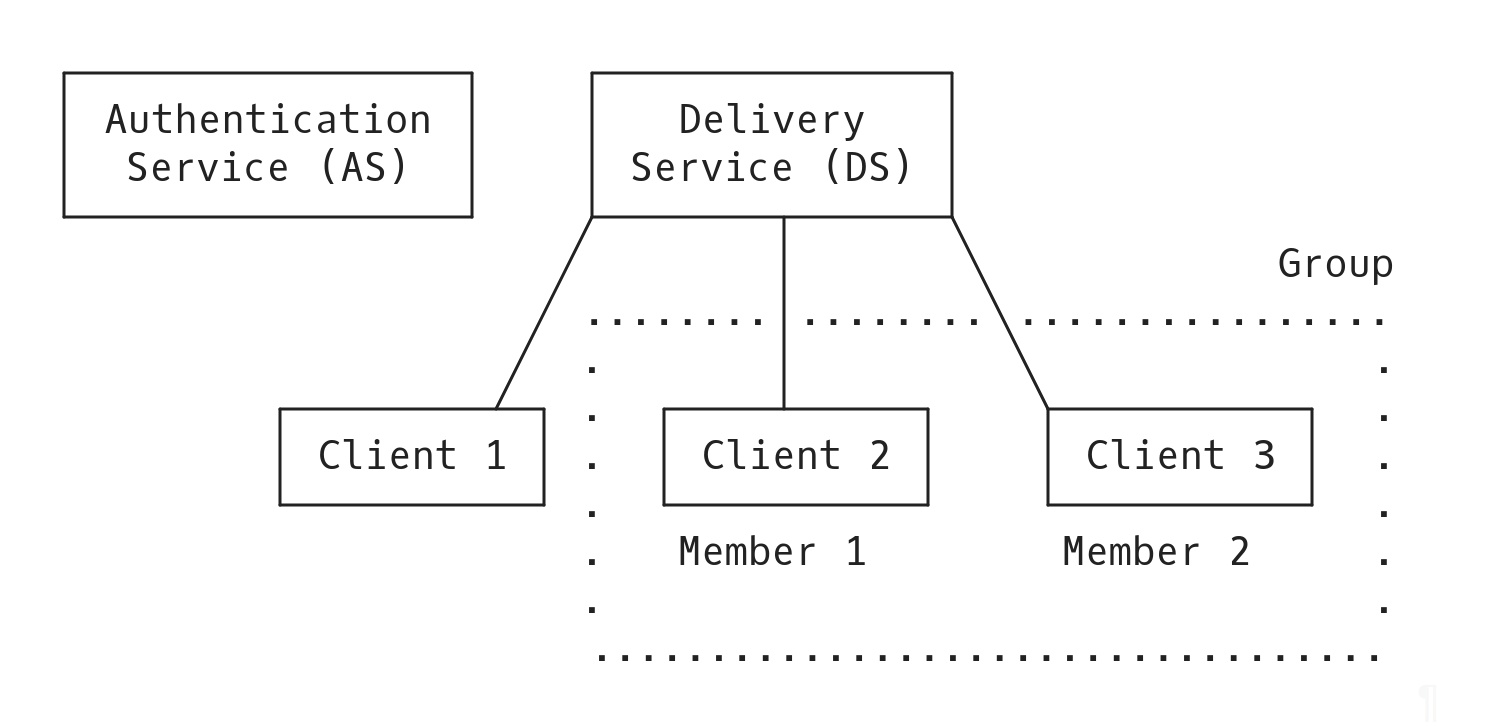

The MLS protocol uses a client-server architecture whereby the "clients" represent group members. There are two kinds of service involved: the Authentication Service (AS) and the Delivery Service (DS).

Architecture

The Authentication Service is responsible for the following:

- Administration of client credentials that bind their identity to cryptographic keys

- Allow clients to verify other clients' credentials represent their identities

- Allow clients to verify two credentials map to the same client

The Delivery Service is responsible for:

- Establishing cryptographic key material for clients for setting up offline messaging

- Routing MLS messages among clients

MLS is also intended to be KEM-agnostic - meaning you should be able to swap out the underlying KEM system with minimal fuss, similarly to how TLS v1.3 does with ciphersuites. This is great news for post-quantum cryptography enthusiasts - you can just swap out X25519 with ML-KEM (formerly CRYSTALS-Kyber) to avoid having Peter Shor discover your dinner plans. It does this using Hybrid Public Key Encryption (HPKE), which uses the KEM to derive a shared secret, a key derivation function (KDF) to turn that secret into a high-entropy key for use with an Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD) algorithm for general encryption.

TreeKEM for dummies

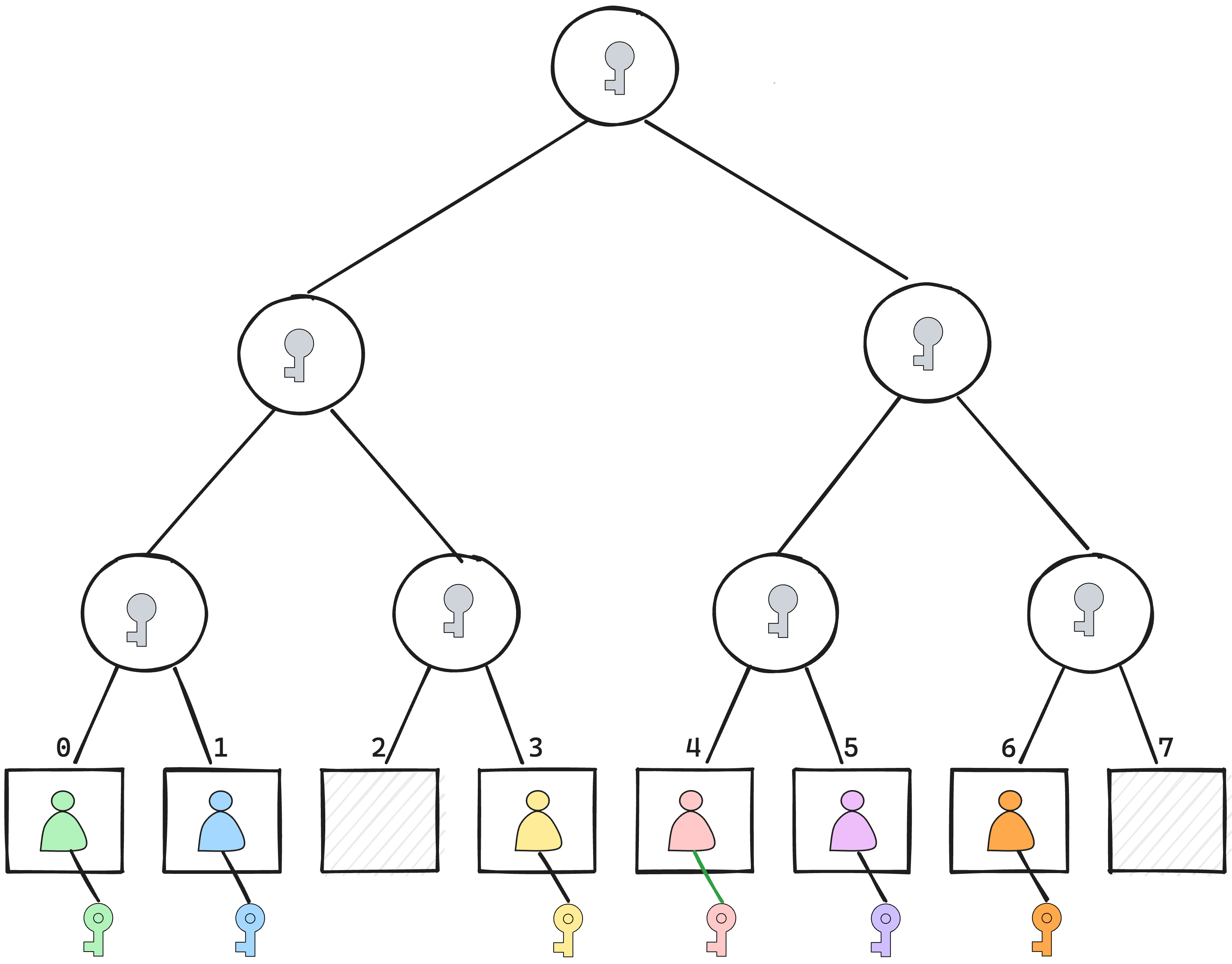

Imagine you have a binary tree, where each leaf node represents a user. Each tree node has a public key (for use with HPKE) and a private key (known by all nodes in that tree's path). Leaf (member) nodes also store a credential that maps a member to one or more identities.

Please note that I'm going to use the terms "group state" and "ratchet tree" interchangeably because I can't decide which one to use.

Tree Paths & Views

Recall each group member is a leaf node. Each internal (non-leaf) node in the tree has a secret derived from the secrets of its children nodes. This trickles up to the top of the tree, where you arrive at the root node and it's corresponding secret. You can imagine the root node's secret (used to derive the epoch secret) is the culmination of the group state, since it's derived from the secrets of all of its members.

Another revelation is that members do not see the whole tree. They only see nodes (and their corresponding secrets) that are in their direct path - that is, the path from their leaf node to the root node at the top. This is called the member's view of the tree.

As a result, every current member knows only what they need to - which includes the root secret used to derive message encryption keys.

Epochs & Tree Lifecycle

The history of a group can be chunked into a series of epochs - cryptographic snapshots of the group at a given time. The "epoch state" of a group at a given time composes its associated key material, secrets and group configuration. An epoch lasts until the group' state is modified; whenever a change is made to the group, the group state/ratchet tree is updated to reflect this, causing the group state to ratchet and triggering a new epoch.

Proposals & Commits

Changes to the group state tree are made through commits. Commits might specify a list of proposals, which describe changes to the ratchet tree; these changes can be addition/removal of group members or refreshing of a member's key material. When a commit is applied, it is sent to each member who will update their view of the tree accordingly (synchronised using TreeSync). These changes "ratchet" the tree, and a new epoch begins. The best part is that it has O(log(n)) complexity in the average case thanks to the magic of binary trees.

How does it come together?

For example, let's say a user is added to the group. A new leaf node is added, and the tree's secrets recalculated. A new epoch begins. Since the tree's root secret (and thus the encryption secrets derived from it) have changed, the new user can read following messages, but not those prior to them joining the group. This is an example of MLS' forward secrecy in action!

The same goes for when a member is removed/leaves the group - their leaf node is pruned from the ratchet tree, triggering a new epoch and leaving the ex-member unable to decrypt further messages. The tree "heals", providing post-compromise security.

You may be wondering what happens if there are no major state changes over a long period of time. Tying the self-healing property to member addition/removal would be pretty bad for post-compromise security; a group having the same membership state for a year would mean the epoch secret

stays the same, and an attacker with access to said secret would be privy to all communications until the next commit! To counter this, MLS suggests client applications automatically refreshing their keys periodically to enforce post-compromise security - although the frequency is "left to the application to determine". It also suggests the removal of members that do not update their keys frequently.

Distributed MLS (DMLS)

A core property of MLS is that it requires a linear commit history. Having out-of-order commits breaks the whole operation - if you happened to receive and apply commit 2 before commit 1, you end up with a different ratchet tree, a different epoch and thus a different root secret to your other group members. Congratulations, you can no longer participate!

This usually isn't a problem - the centralised Delivery Service enforces ordering of commits, making sure no member applies them out-of-order. But what if you have no central Delivery Service? This is the case with the Matrix protocol, which is decentralised by design. Sure, you could retain key material in case you apply commits out-of-order as a "back button", but that would break your precious forward secrecy!

Instead, some very smart folks have come up with Decentralised MLS (DMLS). This makes some slight modifications to the original protocol that allow members to store previous group states securely as a fallback. It utilises "epoch identifiers" and a Puncturable Pseudorandom Function (PPRF) that, once evaluated at an input x, can be "punctured" such that it cannot be evaluated at x again. Instead of storing past secrets, members retain PPRF keys for past epochs such that if they need to roll back a commit they can derive the epoch keys using the PPRF and puncture it once they're "caught up" - compromise of the PPRF key is futile after the PPRF is punctured. Whilst not as forward-secret as vanilla MLS with its strict key deletion schedule, DMLS at least allows it to function over decentralised networks.

Where are we now?

Google is already testing MLS in RCS messaging, and the GSMA has announced the RCS 3.0 standard will support MLS, which companies such as Apple have agreed to adopt. The Matrix foundation is still working on implementing distributed MLS (possibly a fate worse than death), and have demonstrated basic encryption/decryption as well as group state changes. You can check out their progress here.

It's pretty exciting to see the evolution of instant messaging as a secure means of communication, much to the dismay of the intelligence agencies. I'm particularly keen to see how MLS matures over the next few years, as well as how the Matrix ecosystem wrangles the challenge of implementing DMLS alongside the evolving specification.

Further Reading

- Signal - The Double Ratchet Algorithm

- Asynchronous Ratcheting Trees (ART) Paper

- RFC 9420 - The Messaging Layer Security (MLS) Protocol

- Decentralised MLS